The kings of the courtroom

How prosecutors came to dominate the criminal-justice system

http://www.economist.com/news/unite...inate-criminal-justice-system-kings-courtroom

Oct 4th 2014

CAMERON TODD WILLINGHAM was accused of murdering his daughters in 1991 by setting fire to the family house. The main evidence against him was a forensic report on the fire, later shown to be bunk, and the testimony of a jailhouse informant who claimed to have heard him confess. He was executed in 2004.

The snitch who sent him to his death had been told that robbery charges pending against him would be reduced to a lesser offence if he co-operated. After the trial the prosecutor denied that any such deal had been struck, but a handwritten note discovered last year by the Innocence Project, a pressure group, suggests otherwise. In taped interviews, extracts of which were published by the Washington Post, the informant said he lied in court in return for efforts by the prosecutor to secure a reduced sentence andamazinglyfinancial support from a local rancher.

A study by Northwestern University Law Schools Centre on Wrongful Convictions found that 46% of documented wrongful capital convictions between 1973 and 2004 could be traced to false testimony by snitchesmaking them the leading cause of wrongful convictions in death-penalty cases. The Innocence Project keeps a database of Americans convicted of serious crimes but then exonerated by DNA evidence. Of the 318 it lists, 57 involved informantsand 30 of the convicted had entered a guilty plea.

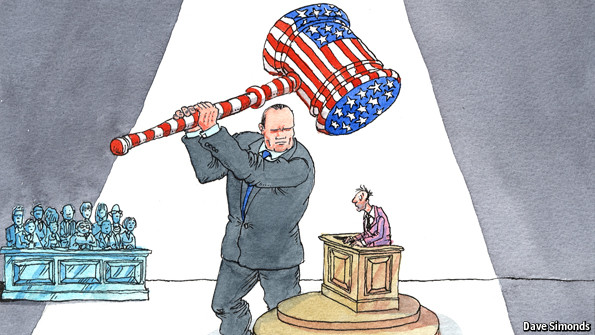

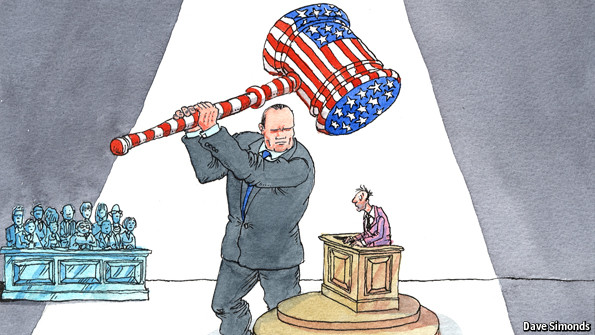

The prosecutor has more control over life, liberty and reputation than any other person in America, said Robert Jackson, the attorney-general, in 1940. As the current attorney-general, Eric Holder, prepares to stand down (see article), American prosecutors are more powerful than ever before.

Several legal changes have empowered them. The first is the explosion of plea bargaining, where a suspect agrees to plead guilty to a lesser charge if the more serious charges against him are dropped. Plea bargains were unobtainable in the early years of American justice. But today more than 95% of cases end in such deals and thus are never brought to trial.

The pressure to plead guilty

Jed Rakoff, a district judge in New York, thinks it unlikely that 95% of defendants are guilty. Of the 2.4m Americans behind bars, he thinks it possible that thousands, perhaps tens of thousands confessed despite being innocent. One reason they might do so is because harsh, mandatory-minimum sentencing rules can make such a choice rational. Rather than risk a trial and a 30-year sentence, some cop a plea and accept a much shorter one.

In such negotiations prosecutors hold all the marbles, says Alexandra Natapoff of Loyola Law School. Mandatory sentencing laws prevent judges from taking into account all the circumstances of a case and exercising discretion over the punishment. Instead, its severity depends largely on the charges the prosecutor chooses to file. In complex white-collar cases, they can threaten to count each e-mail as a separate case of wire fraud. In drugs cases they can choose how much of the stash the dealers sidekick is responsible for. That gives them huge bargaining power. In Florida 4-14g of heroin gets you a minimum of three years in prison; 28g or more gets you 25 years.

In 1996 police found a safe in Stephanie Georges house containing 500g of cocaine. She said it belonged to her ex-boyfriend, who had the key and admitted that it was his. Prosecutors could have charged Ms George with a minor offence: she was obviously too broke to be a drug kingpin. Instead they charged her for everything in the safe, as well as everything her ex-boyfriend had recently soldand for obstruction of justice because she denied all knowledge of his dealings. She received a mandatory sentence of life without the possibility of parole. Her ex-boyfriend received a lighter penalty because he testified that he had paid her to let him use her house to store drugs. Ms George was released in April, after 17 years, only because Barack Obama commuted her sentence.

Under Mr Holder the federal mandatory-minimum regime has been softened for non-violent drug offences. But this has only curbed the power of federal prosecutors, not state ones, and only somewhat.

Another change that empowers prosecutors is the proliferation of incomprehensible new laws. This gives prosecutors more room for interpretation and encourages them to overcharge defendants in order to bully them into plea deals, says Harvey Silverglate, a defence lawyer. Since the financial crisis, says Alex Kozinski, a judge, prosecutors have been more tempted to pore over statutes looking for ways to stretch them so that this or that activity can be construed as illegal. Thats not how criminal law is supposed to work. It should be clear what is illegal, he says.

The same threats and incentives that push the innocent to plead guilty also drive many suspects to testify against others. Deals with co-operating witnesses, once rare, have grown common. In federal cases an estimated 25-30% of defendants offer some form of co-operation, and around half of those receive some credit for it. The proportion is double that in drug cases. Most federal cases are resolved using the actual or anticipated testimony of co-operating defendants.

Co-operator testimony often sways juries because snitches are seen as having first-hand knowledge of the pattern of criminal activity. But snitches hoping to avoid draconian jail terms may sometimes be tempted to compose rather than merely to sing.

Sing or suffer

It is not unusual for a co-operator to have 15 or 20 long meetings with agents and prosecutors. It is hard to know what goes on in these sessions because they are not recorded. Participants take notes but do not have to write down everything that is said; nor do they have to share all their notes with the defence. The time that co-operators and their handlers spend alone is a black hole, says a prosecutor quoted in Snitch: Informants, Cooperators and the Corruption of Justice, by Ethan Brown.

Co-operators have become more common in corporate cases since the Justice Department started bringing in more lawyers experienced in dealing with organised crime. Business cases typically involve mountains of hard-to-fathom documents and turn not on actions but intent. Often, the only way to convince a jury that the defendant knew a transaction was dodgy is to have a former colleague say so.

A common way to recruit co-operators is to name lots of a defendants colleagues as unindicted co-conspirators. (In the Enron fraud case there were 114.) An unindicted co-conspirator can be indicted at any moment; his lawyer will therefore usually advise him, at the very least, not to annoy the prosecutor by helping the defence.

In 2009 James Treacy, a former executive of Monster Worldwide, an employment website, was convicted of illegally manipulating (or backdating) stock options and handed a two-year sentence. He blames slanted testimony by former colleagues turned co-operators. After his release, one of them asked to meet him. Over lunch she tearfully described the governments intimidation tactics, he says. Some were almost comical: broken chairs to sit in; investigators flashing their holstered guns; and long, miserable hours of good cop, bad cop routines, with few water or bathroom breaks. Other techniques were more serious. Prosecutors played the innuendo game, suggesting an indictment if the witness did not co-operate.

Mr Treacy has an axe to grind, but he is not alone in arguing that the system encourages embellishment, or in believing that some prosecutors overstep the mark because they hope to parlay courtroom victories into lucrative partnerships at law firms or platforms to run for public office.

Co-operators feature extensively in insider-trading cases. James Fleishman, a former manager at Primary Global Research, was first approached by FBI agents to help them ensnare his superiors. When he refused to co-operate, insisting he knew of no illegal activity, he became a target himself. His conviction rested on co-operation from two former clients who had been put under immense pressure to be helpful to prosecutors. (They told one they would seek to have him jailed for 50 years if he declined their offer.) In a self-published book, Mr Fleishman argues that the testimony of both was littered with fabrications, including phone conversations that never took place. The co-operators got probation. Mr Fleishman was jailed for 30 months.

There is no way to confirm Mr Fleishmans version of events. There was, however, an intriguing moment at his trial. During cross-examination Mr Fleishmans lawyer complained that his opposing number was mouthing words to a co-operating witness who appeared to be going off-script. The prosecutors response was: If I did that, and Im not disputing what he said Im sorry.

It is not clear how often prosecutors themselves break the rules. According to a report by the Project on Government Oversight, an investigative outfit, compiled from data obtained from freedom of information requests, an internal-affairs office at the Department of Justice identified more than 650 instances of prosecutors violating the professions rules and ethical standards between 2002 and 2013. More than 400 of these were at the more severe end of the scale. The Justice Department argues that this level of misconduct is modest given the thousands of cases it handles.

How prosecutors came to dominate the criminal-justice system

http://www.economist.com/news/unite...inate-criminal-justice-system-kings-courtroom

Oct 4th 2014

CAMERON TODD WILLINGHAM was accused of murdering his daughters in 1991 by setting fire to the family house. The main evidence against him was a forensic report on the fire, later shown to be bunk, and the testimony of a jailhouse informant who claimed to have heard him confess. He was executed in 2004.

The snitch who sent him to his death had been told that robbery charges pending against him would be reduced to a lesser offence if he co-operated. After the trial the prosecutor denied that any such deal had been struck, but a handwritten note discovered last year by the Innocence Project, a pressure group, suggests otherwise. In taped interviews, extracts of which were published by the Washington Post, the informant said he lied in court in return for efforts by the prosecutor to secure a reduced sentence andamazinglyfinancial support from a local rancher.

A study by Northwestern University Law Schools Centre on Wrongful Convictions found that 46% of documented wrongful capital convictions between 1973 and 2004 could be traced to false testimony by snitchesmaking them the leading cause of wrongful convictions in death-penalty cases. The Innocence Project keeps a database of Americans convicted of serious crimes but then exonerated by DNA evidence. Of the 318 it lists, 57 involved informantsand 30 of the convicted had entered a guilty plea.

The prosecutor has more control over life, liberty and reputation than any other person in America, said Robert Jackson, the attorney-general, in 1940. As the current attorney-general, Eric Holder, prepares to stand down (see article), American prosecutors are more powerful than ever before.

Several legal changes have empowered them. The first is the explosion of plea bargaining, where a suspect agrees to plead guilty to a lesser charge if the more serious charges against him are dropped. Plea bargains were unobtainable in the early years of American justice. But today more than 95% of cases end in such deals and thus are never brought to trial.

The pressure to plead guilty

Jed Rakoff, a district judge in New York, thinks it unlikely that 95% of defendants are guilty. Of the 2.4m Americans behind bars, he thinks it possible that thousands, perhaps tens of thousands confessed despite being innocent. One reason they might do so is because harsh, mandatory-minimum sentencing rules can make such a choice rational. Rather than risk a trial and a 30-year sentence, some cop a plea and accept a much shorter one.

In such negotiations prosecutors hold all the marbles, says Alexandra Natapoff of Loyola Law School. Mandatory sentencing laws prevent judges from taking into account all the circumstances of a case and exercising discretion over the punishment. Instead, its severity depends largely on the charges the prosecutor chooses to file. In complex white-collar cases, they can threaten to count each e-mail as a separate case of wire fraud. In drugs cases they can choose how much of the stash the dealers sidekick is responsible for. That gives them huge bargaining power. In Florida 4-14g of heroin gets you a minimum of three years in prison; 28g or more gets you 25 years.

In 1996 police found a safe in Stephanie Georges house containing 500g of cocaine. She said it belonged to her ex-boyfriend, who had the key and admitted that it was his. Prosecutors could have charged Ms George with a minor offence: she was obviously too broke to be a drug kingpin. Instead they charged her for everything in the safe, as well as everything her ex-boyfriend had recently soldand for obstruction of justice because she denied all knowledge of his dealings. She received a mandatory sentence of life without the possibility of parole. Her ex-boyfriend received a lighter penalty because he testified that he had paid her to let him use her house to store drugs. Ms George was released in April, after 17 years, only because Barack Obama commuted her sentence.

Under Mr Holder the federal mandatory-minimum regime has been softened for non-violent drug offences. But this has only curbed the power of federal prosecutors, not state ones, and only somewhat.

Another change that empowers prosecutors is the proliferation of incomprehensible new laws. This gives prosecutors more room for interpretation and encourages them to overcharge defendants in order to bully them into plea deals, says Harvey Silverglate, a defence lawyer. Since the financial crisis, says Alex Kozinski, a judge, prosecutors have been more tempted to pore over statutes looking for ways to stretch them so that this or that activity can be construed as illegal. Thats not how criminal law is supposed to work. It should be clear what is illegal, he says.

The same threats and incentives that push the innocent to plead guilty also drive many suspects to testify against others. Deals with co-operating witnesses, once rare, have grown common. In federal cases an estimated 25-30% of defendants offer some form of co-operation, and around half of those receive some credit for it. The proportion is double that in drug cases. Most federal cases are resolved using the actual or anticipated testimony of co-operating defendants.

Co-operator testimony often sways juries because snitches are seen as having first-hand knowledge of the pattern of criminal activity. But snitches hoping to avoid draconian jail terms may sometimes be tempted to compose rather than merely to sing.

Sing or suffer

It is not unusual for a co-operator to have 15 or 20 long meetings with agents and prosecutors. It is hard to know what goes on in these sessions because they are not recorded. Participants take notes but do not have to write down everything that is said; nor do they have to share all their notes with the defence. The time that co-operators and their handlers spend alone is a black hole, says a prosecutor quoted in Snitch: Informants, Cooperators and the Corruption of Justice, by Ethan Brown.

Co-operators have become more common in corporate cases since the Justice Department started bringing in more lawyers experienced in dealing with organised crime. Business cases typically involve mountains of hard-to-fathom documents and turn not on actions but intent. Often, the only way to convince a jury that the defendant knew a transaction was dodgy is to have a former colleague say so.

A common way to recruit co-operators is to name lots of a defendants colleagues as unindicted co-conspirators. (In the Enron fraud case there were 114.) An unindicted co-conspirator can be indicted at any moment; his lawyer will therefore usually advise him, at the very least, not to annoy the prosecutor by helping the defence.

In 2009 James Treacy, a former executive of Monster Worldwide, an employment website, was convicted of illegally manipulating (or backdating) stock options and handed a two-year sentence. He blames slanted testimony by former colleagues turned co-operators. After his release, one of them asked to meet him. Over lunch she tearfully described the governments intimidation tactics, he says. Some were almost comical: broken chairs to sit in; investigators flashing their holstered guns; and long, miserable hours of good cop, bad cop routines, with few water or bathroom breaks. Other techniques were more serious. Prosecutors played the innuendo game, suggesting an indictment if the witness did not co-operate.

Mr Treacy has an axe to grind, but he is not alone in arguing that the system encourages embellishment, or in believing that some prosecutors overstep the mark because they hope to parlay courtroom victories into lucrative partnerships at law firms or platforms to run for public office.

Co-operators feature extensively in insider-trading cases. James Fleishman, a former manager at Primary Global Research, was first approached by FBI agents to help them ensnare his superiors. When he refused to co-operate, insisting he knew of no illegal activity, he became a target himself. His conviction rested on co-operation from two former clients who had been put under immense pressure to be helpful to prosecutors. (They told one they would seek to have him jailed for 50 years if he declined their offer.) In a self-published book, Mr Fleishman argues that the testimony of both was littered with fabrications, including phone conversations that never took place. The co-operators got probation. Mr Fleishman was jailed for 30 months.

There is no way to confirm Mr Fleishmans version of events. There was, however, an intriguing moment at his trial. During cross-examination Mr Fleishmans lawyer complained that his opposing number was mouthing words to a co-operating witness who appeared to be going off-script. The prosecutors response was: If I did that, and Im not disputing what he said Im sorry.

It is not clear how often prosecutors themselves break the rules. According to a report by the Project on Government Oversight, an investigative outfit, compiled from data obtained from freedom of information requests, an internal-affairs office at the Department of Justice identified more than 650 instances of prosecutors violating the professions rules and ethical standards between 2002 and 2013. More than 400 of these were at the more severe end of the scale. The Justice Department argues that this level of misconduct is modest given the thousands of cases it handles.