How Nigeria stopped Ebola

Oct 20th 2014

http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/10/economist-explains-6

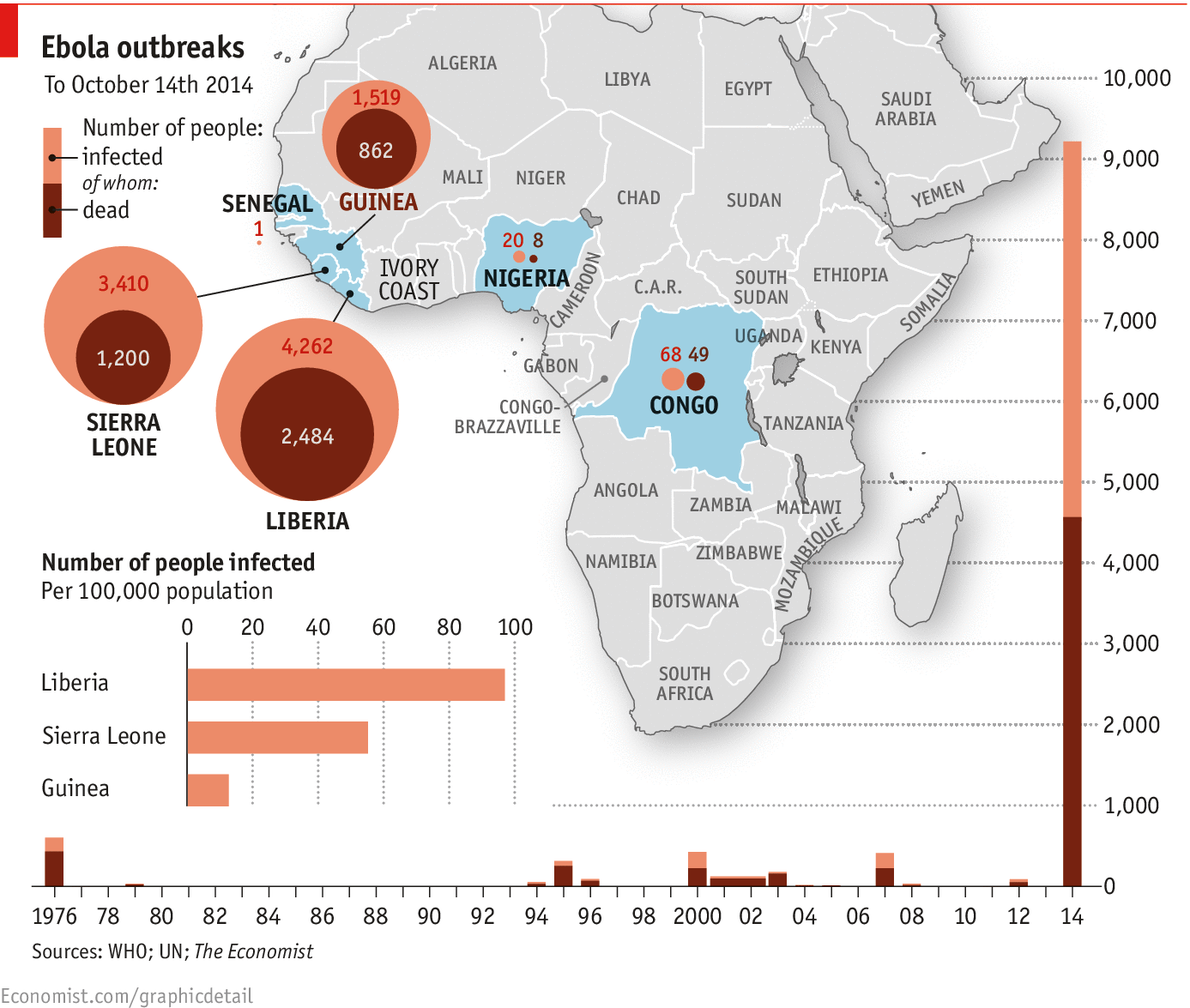

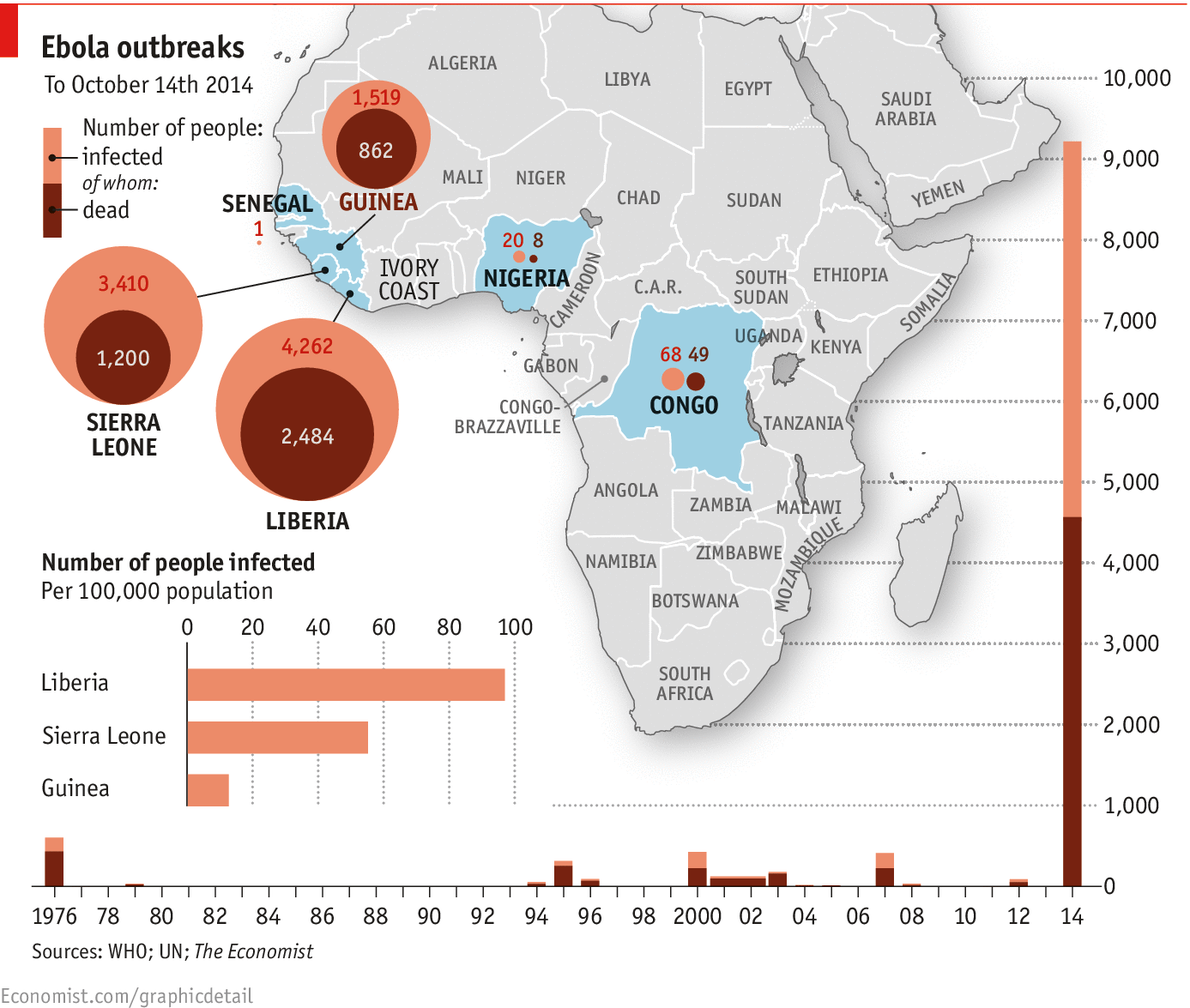

WHEN Patrick Sawyer arrived at Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos, Nigeria's capital, on July 20th he promptly collapsed. About two weeks earlier, he had been exposed to the Ebola virus in Liberia. Now he had brought it to Nigeria. The outbreak resulted in 19 confirmed cases and eight deaths in Nigeria, including that of Sawyer. But unlike Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, where Ebola has so far killed over 4,500 people, Nigeria was able to stop the virus. On October 20th the country was declared Ebola-free. How did it do it?

Nigeria is home to 177m people, the most in Africa. Lagos, its commercial hub, has over 20m residents, many who live in teeming slums. So there was great potential for the disease to spread, and not just inside the country. Thousands of people pass through the international airport in Lagos each day, on their way to China, India and America. Many international businesses have their African headquarters in the city. International health officials feared that an Ebola outbreak in Nigeria would lead to a truly global pandemic.

In some ways Nigeria got lucky. Of the roughly 200 people on the flight with Sawyer, none came down with Ebola. When Sawyer himself insisted on leaving the hospital where he was being treated, a doctor called Ameyo Adadevoh stopped him. She would later die. The government was slow to act, in part because Sawyer was not immediately diagnosed with Ebola. But once the authorities recognised the virus, they were able to mount a robust response. Nigeria has more doctors and hospitals per person than most African countries. It also has teams in place to investigate outbreaks of diseases like cholera and Lassa fever. These tools were simply redirected.

A command centre financed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to fight polio was used to co-ordinate the Ebola response. Experts from America's Centres for Disease Control (CDC) were already training 100 Nigerian doctors in epidemiology, so 40 of them led the process of tracing Sawyer's contacts. The government worked with airlines to find people whom he could have infected. Then health workers repeatedly took the temperature of nearly 900 possible contacts, paying them more than 18,500 visits in total.

“For those who say it’s hopeless, this is an antidote-you can control Ebola,” said Thomas Frieden, the director of the CDC. Other countries at risk can learn from Nigeria's experience. They should be preparing themselves by creating rapid intervention teams and improving their surveillance systems, says Chris Stokes of Médecins Sans Frontières, an NGO. But Dr Frieden warns: “Some countries that could well be the next Lagos still don’t have a clue about how to deal with this.”

Worse, most of the lessons from Nigeria are not applicable to the countries where Ebola is now raging out of control. Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone do not have the same resources and are anyway too late to stamp out the virus quickly. It will be some time before those countries are declared Ebola-free, which means Nigeria-and the rest of the world-are still at risk.

Dig deeper:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/10/economist-explains-6

The Ebola epidemic in west Africa poses a catastrophic threat to the region, and could yet spread further (October 2014)

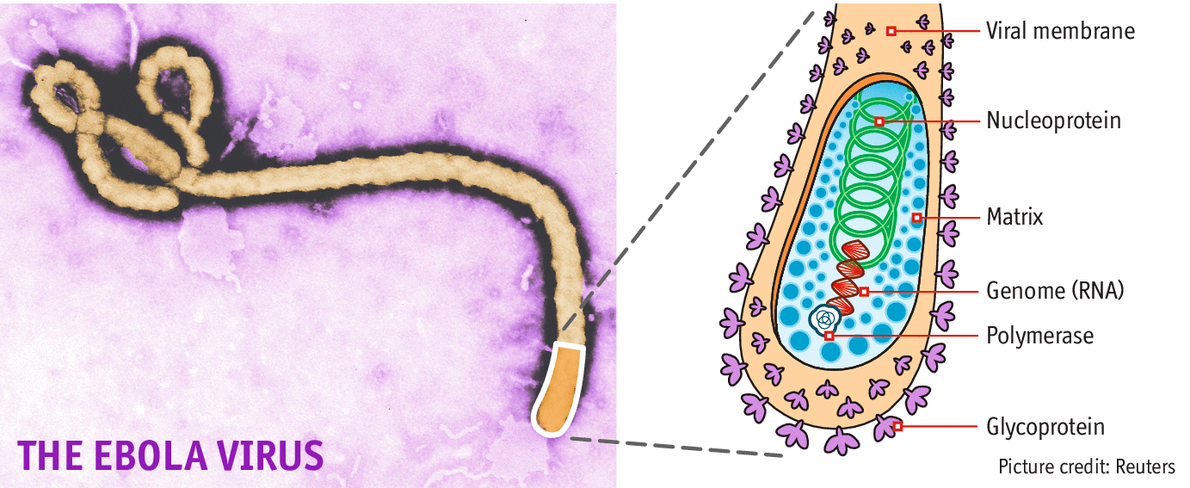

How Ebola kills with just seven genes (October 2014)

Ebola in graphics

Oct 20th 2014

http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/10/economist-explains-6

WHEN Patrick Sawyer arrived at Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos, Nigeria's capital, on July 20th he promptly collapsed. About two weeks earlier, he had been exposed to the Ebola virus in Liberia. Now he had brought it to Nigeria. The outbreak resulted in 19 confirmed cases and eight deaths in Nigeria, including that of Sawyer. But unlike Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, where Ebola has so far killed over 4,500 people, Nigeria was able to stop the virus. On October 20th the country was declared Ebola-free. How did it do it?

Nigeria is home to 177m people, the most in Africa. Lagos, its commercial hub, has over 20m residents, many who live in teeming slums. So there was great potential for the disease to spread, and not just inside the country. Thousands of people pass through the international airport in Lagos each day, on their way to China, India and America. Many international businesses have their African headquarters in the city. International health officials feared that an Ebola outbreak in Nigeria would lead to a truly global pandemic.

In some ways Nigeria got lucky. Of the roughly 200 people on the flight with Sawyer, none came down with Ebola. When Sawyer himself insisted on leaving the hospital where he was being treated, a doctor called Ameyo Adadevoh stopped him. She would later die. The government was slow to act, in part because Sawyer was not immediately diagnosed with Ebola. But once the authorities recognised the virus, they were able to mount a robust response. Nigeria has more doctors and hospitals per person than most African countries. It also has teams in place to investigate outbreaks of diseases like cholera and Lassa fever. These tools were simply redirected.

A command centre financed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to fight polio was used to co-ordinate the Ebola response. Experts from America's Centres for Disease Control (CDC) were already training 100 Nigerian doctors in epidemiology, so 40 of them led the process of tracing Sawyer's contacts. The government worked with airlines to find people whom he could have infected. Then health workers repeatedly took the temperature of nearly 900 possible contacts, paying them more than 18,500 visits in total.

“For those who say it’s hopeless, this is an antidote-you can control Ebola,” said Thomas Frieden, the director of the CDC. Other countries at risk can learn from Nigeria's experience. They should be preparing themselves by creating rapid intervention teams and improving their surveillance systems, says Chris Stokes of Médecins Sans Frontières, an NGO. But Dr Frieden warns: “Some countries that could well be the next Lagos still don’t have a clue about how to deal with this.”

Worse, most of the lessons from Nigeria are not applicable to the countries where Ebola is now raging out of control. Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone do not have the same resources and are anyway too late to stamp out the virus quickly. It will be some time before those countries are declared Ebola-free, which means Nigeria-and the rest of the world-are still at risk.

Dig deeper:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/10/economist-explains-6

The Ebola epidemic in west Africa poses a catastrophic threat to the region, and could yet spread further (October 2014)

How Ebola kills with just seven genes (October 2014)

Ebola in graphics

GC says "Welcome to his world" ...

GC says "Welcome to his world" ...